Case study dilemma and research question

In viticulture, the general dependency on external inputs such as fertilisers and especially pesticides is high. The reduction of synthetic inputs could impact yields and many farmers fear economic consequences.

In France, the research project UNISECO aimed at investigating how to reduce dependency on external fertilisers and pesticides (especially glyphosate) through agro-ecological practices increasing soil ecological services while maintaining the economic viability of farms.

Key characteristics and sustainability issues of the farming system

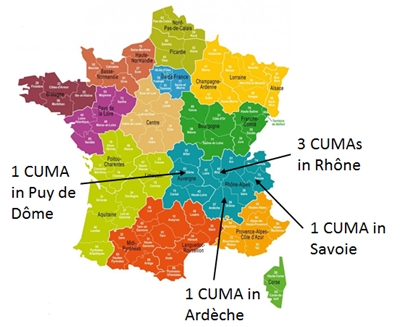

This case study is a network based case study involving several French farm machinery cooperatives (CUMAs) aiming at close collaboration between farmers.

An innovative aspect of the project is the aim to interconnect different territorial groups of farmers. It is therefore a network on two levels:

- at local level, farmers are engaged in each CUMA to share equipment and exchange knowledge;

- at regional level, a group of farmers from different CUMAs, boost the exchange of knowledge and the share of innovative practices and field experiments.

The local and regional networks act as extension services to farmers. This approach comprises: visits of farms, exchanges and debates between farmers, farm machinery demonstrations.

The diagnosis of sustainability conducted in UNISECO with SMART tool shows: a good or average rating for the different sustainability criteria in the economic, social and environmental dimensions:

- The economic dimension exhibits the lowest performance due to internannual variabilities in quantities harvested and low prices in some areas;

- The ratings with regard to social well-being are in general satisfactory;

- With regard to the environmental dimension, the ratings concerning biodiversity and greenhouse gas emissions are average (neither good nor bad). Some farms have also an average rating with regard to water quality.

The majority of current agricultural practices remain conventional with significant use of pesticides (herbicides and fungicides) and chemical fertilisers. However, some farmers are already implementing agroecological practices.

Key actors involved

- Authorities and administrations: Region (Local govnt), Département (Local govnt), Departmental (DDT) or Regional delegation (DRAAF) of Ministry of agriculture and CAP, rural districts, municipalities.

- Farmers and farming organisations: Departmental Federation of CUMA French farm machinery cooperatives, Regional Federation of CUMA, Farmers Union, Atelier Paysan (cooperative for machineries’ self building, Individual Farmers

- Agri-food value chain: Wine Federation/Union, Wine Processors (Cooperative or Private Company), farming Inputs providers (Cooperative or Private Company)

- NGOs, civic society organisations: environmental associations (including management association sur as syndicat de rivière)

- Science, innovation, advisory: Research and University, Education and Training centers, Accountancy firm, Farming machinery dealership

- Consumers and citizens

Agro-ecological practices and sustainability trade-offs

After a long period of reluctance of farmers, society is waiting for rapid changes in farming practices to preserve the environment. Now farmers are more aware about this issue but they need time and support to adapt their practices and systems. Some farmers are already implementing agroecological practices but the majority of them intend to start implementing practices such as: green manure to reduce external fertilisers use; using combined cropping and mechanical weeding to reduce pesticides use (wine shrubs and other crops); testing specific materials for slopes (i.e. rotary spade) to prevent erosion and reduce water evaporation. These emerging practices need to be intensified and encouraged.

Key barriers of implementation of agro-ecological practices

Five barriers towards agroecology have been identified:

- Economic barrier. Excepted for organic farmers, there is no positive price premium for farmers engaged in agroecology. In such a context farmers are not willing to take the risk of reducing the economic sustainability by implementing more environmental practices that are often considered as less productive.

- Governance barrier. Governance of viticulture and its products is separated in three levels: agri-food value chain actors; authorities and public administrations; agricultural advisors. Agroecology is mainly promoted by authorities and there is not enough links and consistency between levels. Farmers face contradictory injunctions which are unmanageable at farm level.

- Technical barrier. Reducing the use of pesticides or chemical fertilisers is not so easy. This is especially true for the reduction of pesticides on steep slopes where mechanical weeding is often impossible or requires specific machineries.

- The fourth factor is the insecurity related to an agro-ecological approach of vine diseases and pests. A management based on ecological services is more risky for the yield and the quality of grapes than a management based on chemical treatments.

- Finally, the last barrier is related to climate change. Current climate change, with droughts and high temperature has soon consequences on the quality and on the quantity of wines. In such a context, changing their practices towards agroecology without any information about their consequences in a new climatic context is a huge concern.

Key actions and strategies to overcome barriers

Farmers mainly adapt their practices to quality schemes production rules, purchasers' requirements and markets' expectations. Including the environmental expectations of consumers in purchasers' requirements is necessary to enable changes in farmers' practices at a broad scale. It can be done by relevant private and public product specifications (such as broadening rules for geographic indication).

Collective action, such as the CUMAs (farm machinery cooperatives) networks of farmers, fosters the experimentation of new practices and the exchange of good practices. There are different policy instruments already in place that enable to empower groups of innovative farmers. Instruments aiming to include in such networks the numerous farmers currently outside any network would be helpful. Testing instruments to foster cooperation between farmers and non-farming stakeholders (local authorities,…) for implementing crop diversification or agri-environmental measures is a promising approach.

Key lessons learnt

After a long period of reluctance of farmers, society is waiting for rapid changes in farming practices to preserve the environment. Now farmers are more aware about this issue but they need time to adapt their practices and systems. There is a need to rebuild trust through mutual exchanges and a better knowledge of each other.

Collective action, such as the CUMAs networks, fosters the experimentation of new practices and the exchange of good practices. This mode of operation empowers farmers to handle technical obstacles and to get public support but remains insufficient to tackle other difficulties as the economic barriers.

References

- Ostrom E. (2009). A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science, July 24th 2009, 325 (5939): 419-422.

- Prazan J., Aalders I., 2019. Deliverable Report D2.2 : Typology of AEFS and practices in the EU and the selection of case studies. UNISECO project, 57p.

- Guisepelli E., Fleury P., Vincent A., Aalders I., Prazan J., Vanni F. 2018 Deliverable Report D2.1 : Adapted SES framework for AEFS and guidelines for assessing sustainability of agricultural systems in Europe. UNISECO Project - Conceptual framework of socio-ecological systems for the sustainability assessment of (ecological) farming systems - WP 2- 2.1 Month 6), 54p.

Download

- French summary of the project and the case study in France: Comprendre et améliorer la durabilité des systèmes agro-écologiques en Europe

- UNISECO H2020 issue brief: Connecting farmers to foster the adoption of agro-ecological practices

- UNISECO H2020 policy brief: Viticulture and agroecology (France). Cooperation between farmers to foster agroecological practices in viticulture

- UNISECO H2020 policy brief: Viticulture et agro-écologie (France). Coopération entre exploitants viticoles pour promouvoir les pratiques agro-écologiques en viticultre

Related newsitems