Case study dilemma and research questions

The case study dilemma was centred around the economic viability of small-scale farming, including identifying better economic and policy-related solutions for smallholder farmers, while maintaining beneficial traditional farming practices and the resulting cultural landscapes; in short, finding a balance between development and cultural and biodiversity conservation.

Farm-level research directions:

1) How do farms, including small-scale farms, perform on the three dimensions of sustainability - economic, social and environmental, in the two study areas?

Territorial-level research directions:

2) How can Transylvania and Maramures continue to provide their people and consumers in general with quality food, a cultural identity, and to harbour ecological treasures with wide societal value?

National-level research questions:

3) How can we reward smallholders for their contribution to biodiversity and landscape custodianship and increase their economic viability through (better) targeted market and policy measures and incentives and better regulations?

Key characteristics and sustainability issues of the farming system

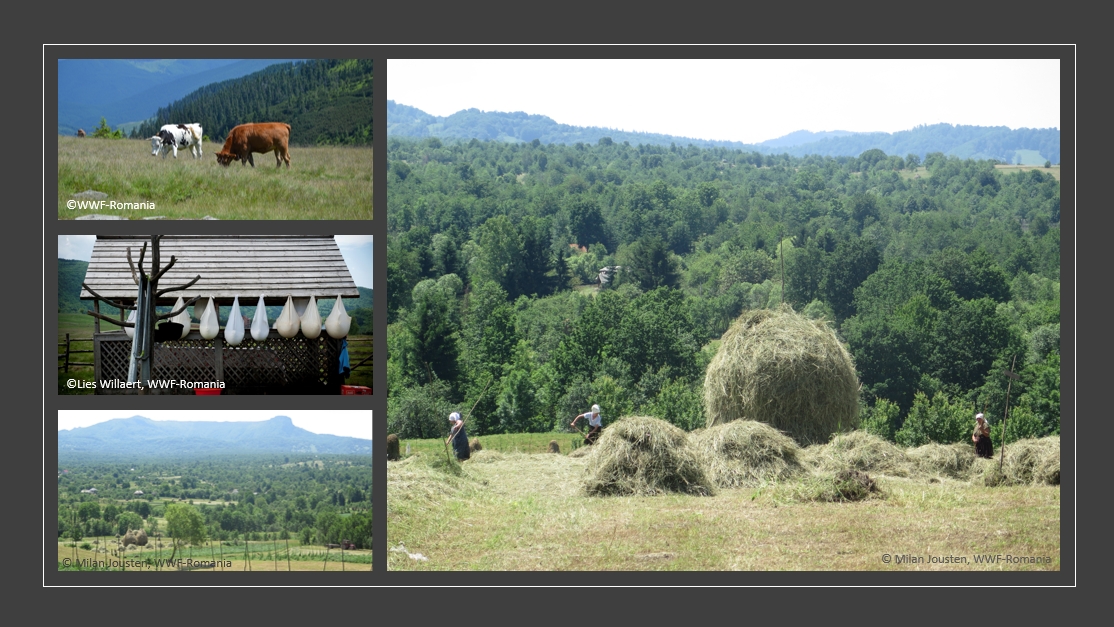

The case study in Romania focused on Maramures and the Transylvanian Highlands, two distinctive geographic regions but having multiple common landscape and socio-economic traits - fragmented agricultural landscape, mosaic patches of semi-natural grasslands created and maintained by traditional livestock grazing systems, small plots of cultivated land with rather low intensity. The two areas are High Nature Value Farmlands (HNVF). The mosaic cultural landscape results from the long-term, still surviving traditional farming practices. In addition to such practices supporting a diverse land cover, they also have essential benefits for biodiversity, supporting the presence, abundance and diversity of plant and animal species. The input of pesticides and fertilisers is relatively low, while the amount of manual labour to work the land is still high. Many farmers still plough their land with the help of horses, weed their crops by hand, rotate crops and manually cut hay for their livestock. While being labour-intensive, these techniques maintain soil health and enable plants to spread their seeds and re-emerge year on year, and wild animals to survive, even thrive within the cultivated landscape. Then, traditional silvo-pastoral techniques have created historic wood pastures, which are an emblem of the area. In wood pastures, both forest species and grassland species thrive because of the combination of woody vegetation and grassland. Also, traditional livestock herding knowledge helps to keep under control the risk of predation from bears and wolves and so the level of human-wildlife coexistence is still relatively stable.

Despite the many benefits of traditional and small-scale farming, Transylvania and Maramures are changing quite rapidly due to social dynamics, market pressures and factors related to public policies, and this poses a range of challenges for sustainability in general, as well as for biodiversity and natural resources in particular.

The survival of the cultural landscape and the biodiversity it harbours is dependent on continued traditional management practices by small-scale farming communities, including on extensive cattle farming to maintain hay-meadows. As long as traditional management provides at least decent local incomes, the farmers will preserve the habitats and associated species, as they have done for centuries.

Key actors involved

- Adept Foundation is carrying out a longstanding integrated programme linking economic and social benefits with biodiversity conservation, raising local capacity for good landscape management and advocating for public agricultural policies for HNV farming and farmers.

- Local Action Group Târnavelor Hills was established as a public-private partnership in 2007 under the LEADER programme to develop and implement a local development strategy through a bottom-up approach.

- Leuphana University Lueneburg: The Sustainable Landscapes Group is an academic research team at Leuphana University Lüneburg (Germany) who authored 3 of the most important recent books about the sustainability of Southern Transylvania - Sustainable landscapes in Central Romania, The future of people in Southern Transylvania, and Balance Brings Beauty: A Shared Vision for Southern Transylvania.

- The Mihai Eminescu Trust Foundation has dedicated itself to the restoration and protection of the historical Transylvanian built and cultural heritage.

- Association APAVIE Valeni: Association of HNV farmers in Maramures, involved also in projects promoting the HNV landscape and HNV products from Historical Maramures.

- Association of Traditional and Ecological Producers Maramures: Actively producing and promoting traditional and ecological products from Maramures (honey, orchard fruit, cheese, meat products), and participating in open markets in Romania.

- Maramures Museum Sighetu Marmatiei: Actively involved in the preservation and promotion of natural science and traditional living, including the traditional architecture in Maramures

- Local Action Group Mara-Gutai: Also functioning under the LEADER programme, identifying and financing projects of local relevance and promoting traditional, ecological agriculture

- Maramures County Council, external relations office: Synergic initiatives as they implement projects such as Food Chains for Europe (Interreg), where they target the promotion of traditional products (including food)

- The County Councils of Brasov, Mures and Sibiu

- EcoLogic Association, Maramures: Manager of the ecotourism destination Mara-Cosau-Creasta Cocosului/EcoMaramures, much interested in and actively working for the promotion of traditional products and the HNV landscape

- Mioritics Association: Manager of the ecotourism destination Transylvanian Highlands

- Farmers and farmers associations

- Other key actors: public authorities and administration - local town halls, the Agency for Payments and Interventions in Agriculture, the Sanitary-Veterinary and Food Safety Department; the Pastures Research and Development Centre Brasov; consultancy companies; HoReCa.

AGRO-ECOLOGICAL PRACTICES AND SUSTAINABILITY TRADE-OFFS

Crop rotation on arable land, in conventional cattle farms, where the resulting feed ensures half or most of the animals’ diet, as grazing is also part of the system but to a lesser degree. Moreover, the crop rotation practice includes legumes, with lucerne/alfalfa or a combination of lucerne and common vetch. This practice was found in three of the 10 farms analysed in the case study. The main benefits are for soil quality and a reduced need for pesticides and chemical fertilizers and self-sufficiency in animal feed, while there could be an increased need for labour and/or machinery/equipment and facilities.

Producing and/or using compost: Traditionally, in Romania and in the case study, compost is made from manure and it is sourced from one’s own farm and/or from neighbouring farms. The compost promotes the growth and health of plants and roots and adds organic matter to the soil, while reducing dependence on external, synthetic fertilisers, but there are also disadvantages associated with emissions and water pollution from the improper storage of manure during fermentation, from usage at inappropriate times of the year or before it turns into compost.The compost has also been treated in the study as an opportunity of extra income generation at farm level; it can be a development component in the farm and could be coupled with other activities (e.g. educational programmes).

Orchard meadows (especially in Maramures) and wood pastures (especially in Transylvania): These agro-ecological habitats, with their corresponding management practice through extensive grazing, traditional hay-making, fruit harvesting have been found explicitly in four of the farms analysed in the case study. However, they are emblematic features of the landscape in Maramures and Transylvania. These landscapes present a higher carbon stocking potential, better animal welfare and health, better conditions for cross-pollination and maintenance of plant genetic diversity, high biodiversity (e.g. birds and insects); these also allow for the diversification of farm produce and related incomes (e.g. beekeeping, selling fruits), but this involves labour and investment costs, and having good entrepreneurial skills.

Diversification/Mixed farming (livestock, pasture and crops): Almost all farms studied in the project are mixed farms, combining livestock with crops cultivated on farm owned/managed arable land, and/or grasslands for grazing or hay-making; however, the level of diversification varies and the combination of activities from farm to farm is different. Diversified, mixed farming is a typical trait of family-farming and semi-subsistence farming in Romania which also covers own consumption needs, and although more complex and labour intensive, it allows for resources to be reused, recycled in the farm in a circular system, minimising the use of external inputs (e.g. chemical fertilisers, external feed for animals), and allows for better risk management and economic resilience because of the diversified income streams provided by the various farm produce. Mixed farms also provide the context for the perpetuation of indigenous knowledge associated with managing self-sufficient farms.

Extensive grazing: Of all 10 farms in the case study, three farms are using this practice. Moreover, one of them is certified organic. This system is one that is characteristic of the hilly lands, where cattle have been raised from generation to generation in family farms according to certain customs. The organic certification is a supplementary credential to their environmentally-friendly mode of operation, a market mechanism that helps them to differentiate from other products and that could increase the chances of a better income on a market that doesn't place enough value on farms and products that are beneficial to the environment and to local economies.

KEY BARRIERS OF IMPLEMENTATION AGRO-ECOLOGICAL PRACTICES

- Lack of public funding and public infrastructure to support proper management, production, sale and usage of compost

- Insufficient level of information and training amongst farmers related to composting

- Lack of information and advisory services for the use of agro-ecological practices and a lack of a differentiated information/consultancy service system for small, medium and large farms

- Agricultural education not adapted to the present and future challenges related to climate change and biodiversity loss

- A preference for the easily accessible synthetic fertilizers

- The insufficient or even lack of storage and processing facilities/infrastructure to create finite food products from raw ingredients

- Hygiene and food safety standards/regulations that are too strict, complex and bureaucratic for small producers

- Insufficient or even lack of market access for local and small producers

- Eligibility criteria for (CAP) area-based direct subsidies which come with an obligation to clear the (woody) vegetation from the agricultural land if it exceeds 100 square metres of land coverage

- Public subsidies (CAP) calculated and allocated per animal head, without limits, which can lead to overgrazing

KEY ACTIONS, STRATEGIES TO OVERCOME BARRIERS

An integrated package of new policy, knowledge transfer and market tools for mainstreaming compost and enhancing nitrogen use efficiency:

- transfer of knowledge and good practice, going beyond classic trainings to stimulate free discussions, peer-to-peer dissemination and the power of example (demonstration farms), through the emerging AKIS system, which should feature a central digital information hub (and an associated mobile app);

- a national information and consultancy service system catering to different classes of farms and supporting the achievement of economic efficiency through the use of various agro-ecological practices (e.g. for chemical substitution) that come also with a number of soil improvements; advisory services should also be structured at commune level, adapted to the local realities and deploying multi-disciplinary knowledge and expertise including on the adaptation of practices to local climatic conditions, plant health, soil health, biodiversity and ecosystem services;

- investments to be made by town halls for public composting facilities including through the EAFRD, e.g. the construction of local communal manure storage platforms and usage fees set through a decision of the local council

- a dedicated funding measure for individual farm manure storage platforms and equipment, through the EAFDR, which can be also turned by the farms into an additional business avenue (i.e. selling good quality compost)

- a wide-scale use of a simplified fertilisation plan in small farms, and the mandatory coupling of fertilisation plans with regular soil testing and monitoring in large farms, which could be part of an IT application for nutrient management integrating details about the farm, results of soil studies with spatial and temporal references, crops used and production targets, indications on limits and requirements relevant to nutrient management - a complete picture of the nutrient balance in a given farm.

Promotion and awareness campaigns about the quality and provenance of food products, what certain logos represent and what these logos do really protect. The consumer must be educated for responsible consumption.

Cooperation between all actors in the field and beyond (nutrition and health), from research institutes, NGOs/associations, universities, consultants/advisors and experts, and public administration and institutions, combining theory and information with the practical part. The Ministry of Agriculture should also work together with the Ministry of Education, as the agricultural curriculum should be constantly updated taking into account the technological developments and nature-based solutions to common challenges.

Provisions regarding vegetation cover on agricultural land should be changed to allow a higher limit and flexibility depending on the biogeographical area and the typology of vegetation and trees that are found in the respective area. An inventory of trees on the pasture was also proposed, to keep track of and protect the most valuable ones. Plus, farmer associations should be educated to maintain and clean the land selectively and in accordance with ecological science.

Mobile processing units and common cold storage and processing units built by farmer associations and producer groups, and by town halls. Mayors could invest in collective storage, processing, slaughterhouse infrastructures at local level, for the benefit of the community, including for job creation, and the income generated could be further re-invested in the community.

The hygiene and safety regulations and administrative burden should be simplified for small producers - e.g. the locker room, simplification of the approval process which is too bureaucratic and time-consuming.

The public procurement legislation should be improved to favour local produce coming from extensive farms, smallholders and agro-ecological food systems in public food programmes (e.g. school food programmes) and in the supply of public institutions (e.g. canteens), which could be achieved by improving the evaluation and selection criteria for products. This could also include other recommendations stemming from the EU green procurement guidelines.

There should be a balance/equivalence between subsidies in the Member States, as the subsidy has an impact on the market price, creating unfair competition for local producers who cannot price-match.

KEY LESSONS LEARNT

- Agro-ecological practices require additional effort, understanding the complexity of the system, the need to integrate the various components of the system and to acknowledge the fact that economic benefits are not immediate; to this end, the AKIS and improved knowledge and advisory services are of critical importance; agro-ecology creates in turn the context for long-term balanced and holistic development and environmental sustainability.

- Consumers need to be educated to open up towards local producers and traditional or alternative food distribution channels, to understand the work behind food production and to be willing to create a consumer-producer communion.

- The small, medium-sized and mixed farms must be preserved for an integrated landscape level approach, part of the rural tourism concept and part of a regional/territorial strategy. There is a need for people with vision in decision-making positions and a need for examples of functional good practices.

- To ensure small and medium-sized farms survive, there is a need for strong advocacy on a national and European level by regularly participating in policy-making and monitoring committees, a need for opinion leaders and a long-term vision, and for cooperation between organisations.

- Doing things together rather than in an individualistic manner is part of the solution for boosting the economic performance of the various forms of agro-ecological practice. Farmers/producers need to set-up or join associative structures in order to gain visibility and power in the food chain and in policy-making, and in order to make investments more easily; and local authorities need to gear up their capacities to create collective infrastructures to integrate production, processing and delivery of food outside the production area.

- It seems that the element of “undesired effects” of public policies and funding instruments is not regarded to be as important as their “efficiency”, “targeting” or “feasibility”. The underestimation of the potential undesired effects can create lock-ins with long-term effects and an additional barrier to transition.

- Sanctions should always be coupled in their application with advice on how to correct and improve a certain practice, thus supporting ongoing knowledge building.

- The LEADER Programme should still be treated and funded as a key instrument, as it’s based on a territorial, grassroots approach and a public-private partnership model, for an active participation of the local population and various stakeholders in the planning, decision-making and implementation of the strategies necessary for the development of an area.

Downloads

Related newsitems

https://uniseco-project.eu/news/101/ro-case-study-workshop-discussed-the-governance-dimension-of-agro-ecology

https://uniseco-project.eu/news/44/eip-agri-workshop-small-is-smart-innovative-solutions-for-small-agricultural-and-forestry-holdings