The role of research and innovation in agro-ecological farming systems

If the overall objective of agro-ecological farming systems is achieving a system re-design based on agro-ecological principles, it is clear that the technical improvement of farming practices is not sufficient. Such a re-design requires collective thinking, the involvement of new actors and different forms of coordination between stakeholders.

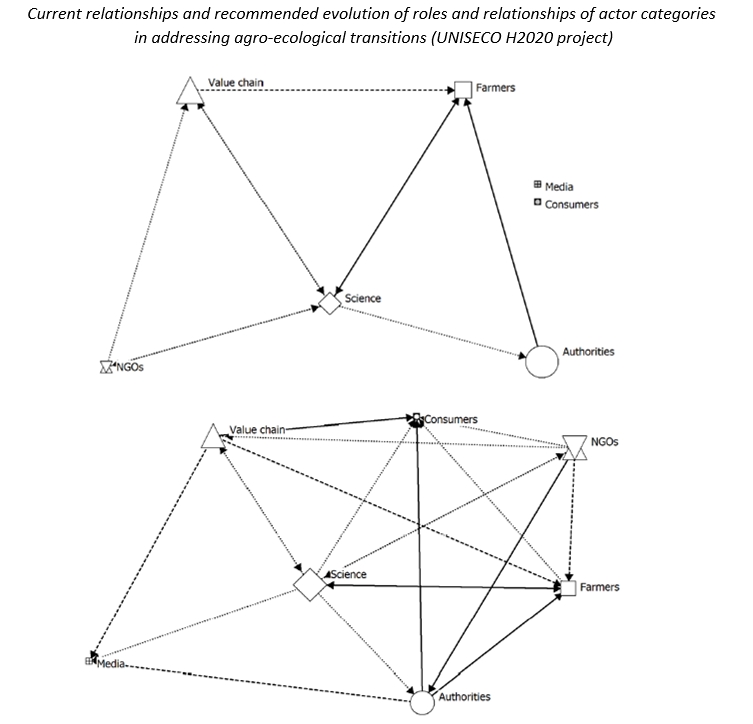

Science and innovation are at the heart of not only advancing knowledge, know-how and technology development of agro-ecological transitions. We learnt from the UNISECO Case Studies that research, innovation and advisory actors also have a central role as mediators in the science-policy-practice interface. In the UNISECO Case Studies there is already an active engagement in the networks of the value chain, farmers and public sector actors. However, NGOs and other civil society organisations were observed having limited roles, with very reduced or no interaction at all with farmers and authorities. In most case studies media is a missing actor, only few case studies pinpointed media as a crucial node of the network, for spreading knowledge. To effectively mediate the adoption of agro-ecological farming systems via an increase in the demand, consumers need proper education about the different options available, in terms of their potential benefits for the environment and for rural development. Science has a role in contributing with knowledge to environmental and sustainability education, and translating new advancements into messages in the specific language of various actors, to assist policy and value chain actors including consumers in the transition towards sustainable food systems. This is a clear message from the analysis of categories of actors currently involved in supporting agro-ecological farming systems in the 15 UNISECO case studies.

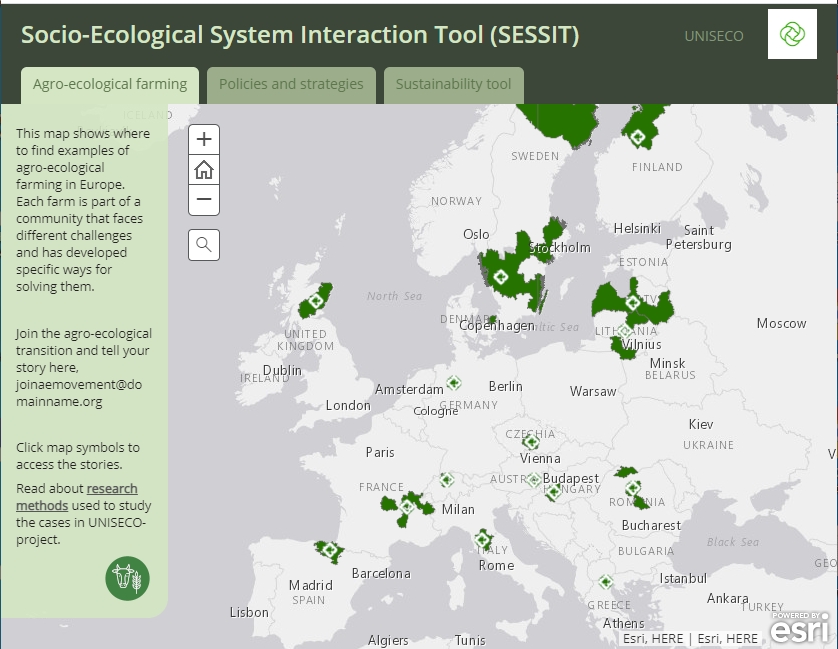

EXPLORE THE DETAILS OF OUR CASE STUDIES BY CLICKING ON THE RESPECTIVE PARTS OF THE OVERVIEW MAP AT THE BOTTOM OF THIS PAGE.

Our evidences collected in the field also suggest that in the evolution of the roles and relationships of actor categories in order to improve how the key dilemmas of agro-ecological transitions should be addressed, the actors identified under the science and innovation category (including AKIS and advisory services) should improve how they involve actors of the media and consumer to stimulate new forms of learning and knowledge production. This will raise public consciousness, people’s empowerment and political action to facilitate the transition towards agro-ecological farming systems. Especially, evidence from the case studies suggest that skilled farm advisors (e.g. on agro-ecological practices) are necessary for farm level adoption of AE practices. Then targeting incentives to advisors might improve their ability to drive agro-ecological innovation, e.g. by supporting advisors’ further education. Education has a crucial role itself, especially for the future generations of farmers and advisors. The diffusion of AE programs in formal secondary and tertiary education is uneven throughout Europe. This is due to many institutional and cultural diversities across countries; overcoming those differences may help improving the knowledge base of producers and practitioners. Besides, extension services did not show up as relevant themselves in any of the case studies. This might be due to agroecology not being a formalised agricultural method yet. Often, extension is associated with the activity of farmer associations, which sometimes tend to be the voice of risk averse farmers. The transition towards agroecology is a knowledge-intensive process, which, to date, has not guaranteed producers a better position on the market of their products, compared to other types of sustainable farming system. This is due to a difficulty in the identification of clear-cut criteria to differentiate the products on the market and to communicate that difference to the bulk of consumers.